Pandemics top national risk-management frameworks in many countries. For example, pandemic influenza tops the natural hazards matrix of the , and emerging infectious diseases are tagged as of considerable concern. Seen as a medical problem, each outbreak of a potentially dangerous infection prompts authorities to ask a rational set of questions and dust off the menu of response options that can be implemented as needed in a phased manner.

Reality, however, is generally more disruptive, as national governments and supranational agencies balance health security and economic and social imperatives on the back of imperfect and evolving intelligence. It’s a governance challenge that may result in long-term consequences for communities and businesses. On top of this, they also need to accommodate human behavior.

Management Dilemmas and Falling Trust

The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is no exception. The disease — an epidemic that could become a global pandemic — emerged in a densely populated manufacturing and transport hub in central China and has since spread to 29 other countries and regions (as of February 20, 2020), carried along by Chinese New Year and international travel.

In contrast to the Western Africa Ebola emergency of 2013-2016 — more deadly but less contagious, arguably more isolated, and eventually contained in part by richer countries putting money into Africa — COVID-19 presents larger, more interdependent economies with management dilemmas. It has also surfaced at a time of , with national leadership under pressure from growing societal unrest and economic confrontations between major powers.

Effective governance of cross-border crises such as pandemics involves preparedness, response and recovery at local, national and international levels.ĚýÂ show many countries, especially in regions where new pathogens might emerge, are not well-equipped to detect, report and respond to outbreaks.

Denial, Cover Ups and Governance Failures

Response strategies vary, for example: playing up or playing down crises and staying open for business as long as possible versus seeking to reopen quickly. COVID-19 has highlighted tendencies in many countries to deny or cover up red flags in order to avoid economic or political penalties, but this approach can misfire.

With tens of millions of workers now in quarantine and parts in short supply, China is struggling to get economic activity back on track. Countries with well-honed crisis risk-management arrangements are faring better at slowing the spread of infection, although that does not make them immune to political and economic pressures.

COVID-19 has also shown how governance failures may involve inaction or over-zealous action by ill-prepared authorities scrambling to maintain or regain stability. Both ends of the spectrum undermine trust and cooperation among citizens and countries. Centralized control measures may seem necessary to stop or delay the spread of the virus and compensate for weak individual and community resilience, but they may also cause harm.

in cities or cruise ships  those under lockdown and  as people experience stress, anxiety and a sense of isolation and loss of control over their lives.ĚýTravel bans result in social, economic and political penalties, which can discourage individuals and government bodies from sharing information and disclosing future outbreaks. Weak or overwhelmed health systems struggle to limit the spread of infection or cope with surging care needs, further reducing confidence in the competence and character of the institutions and individuals in charge.

Panic Spreads Faster Than Pandemics

Social media poses a further challenge to trust: Panic spreads faster than pandemics, as global platforms amplify uncertainties and misinformation. Emotionally visceral content from anyone, such as data, anecdotes or speculation, that sparks fear can go viral and reach far more people than measured, reassuring advice from experts. Even in the absence of human or automated trolls seeking attention or disruption, well-meaning individuals can spread panic worldwide by  early, provisional or context-free information. Such fear will fray citizens’ trust in governments’ ability to protect them from risk and increase the likelihood of psychologically defensive and societally damaging measures such as Ěý˛ą˛Ô»ĺĚý.

What’s the Impact on Business?

Where a stringent policy response is deemed necessary, business will inevitably be impacted, with both near-term effects and less-expected longer-run consequences.

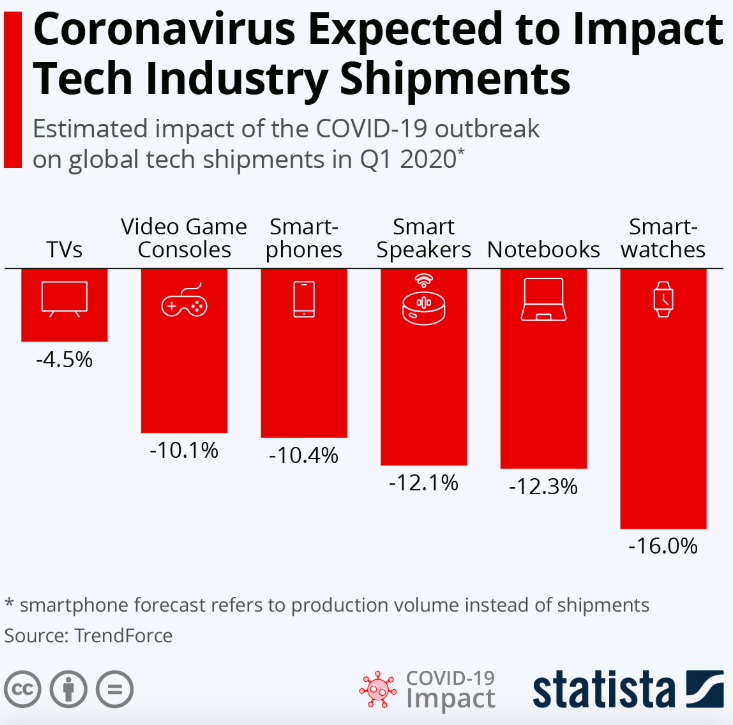

- Travel restrictions and quarantines affecting  have left Chinese factories short of labor and parts, disrupting just-in-time supply chains and triggering sales warnings across ,Ěý and other industries.

- Commodity prices have declined in response to a fall in China’s consumption of raw materials, and producers are considering .

- The mobility and work disruptions have led to , squeezing multinational companies in several sectors including ,Ěý,Ěý,Ěý,Ěý.

Overall, China’s GDP growth may slow by 0.5 percentage points this year, taking at least 0.1 percentage point off of global GDP growth. This will ripple through developed and emerging markets with high dependencies on China — be that in the form of trade, tourism or investment. Some of these countries exhibit pre-existing economic fragilities, others (acknowledging an overlap) have weak health systems and thus lower resilience to pandemics. Many Asian and African countries lack surveillance, diagnostic and hospital capacities to identify, isolate and treat patients during an outbreak. Weak systems anywhere are a risk to health security everywhere, increasing the possibility of contagion and the resulting social and economic consequences.

Why Business Should Invest in Pandemic Resilience

Epidemics and pandemics are hence both a standalone business risk as well as an amplifier of existing trends and vulnerabilities. In the longer run, COVID-19 may serve as another reason — besides protectionist regulations and energy-efficiency needs — for companies to reassess their supply chain exposure to outbreak-prone regions and to .

Businesses may also have to contend with intensifying political, economic and health security risks — for example, resumption of trade hostilities between China and the United States. A prolonged outbreak or economic disruption could fan public discontent in Hong Kong and mainland China, prompting repressive measures that stifle innovation and growth. Stumbling growth in emerging markets may fail to absorb fast-growing workforces, leading to societal unrest, political uncertainty and an inability to invest in health systems.

Beyond standard  related to business operational continuity, employee protection and market preservation, businesses — and countries — should take a fresh look at their exposure to complex and evolving interdependencies that could compound the effects of pandemics and other crises. Given the  of pandemic preparedness, once COVID-19 is contained, much of the world is likely to return to complacency and remain under-prepared for the inevitable next outbreak. Businesses that invest in  to emerging global risks will be better positioned to respond and recover.

A version of this piece originally appeared on the World Economic Forum’s .Ěý

.jpg.imgix.profileSmall.jpg)

402x402.jpg.imgix.threeColumnTile.jpg)